By Irati Oliega Aiesta

More than half a century on, 2022 saw the opening of the very first Article-2 compliant investigation into the death of 14-year-old Desmond ‘Dessie’ Healey, an inquest that has continued in 2023 at Banbridge Court House. Relatives For Justice has long been supporting Dessie’s twin brother, Ted, as well as the wider Healey family, in their quest for truth and justice – not least in this long-awaited process through the coronial system which, in some instances, can be emotionally challenging and feel hostile for families.

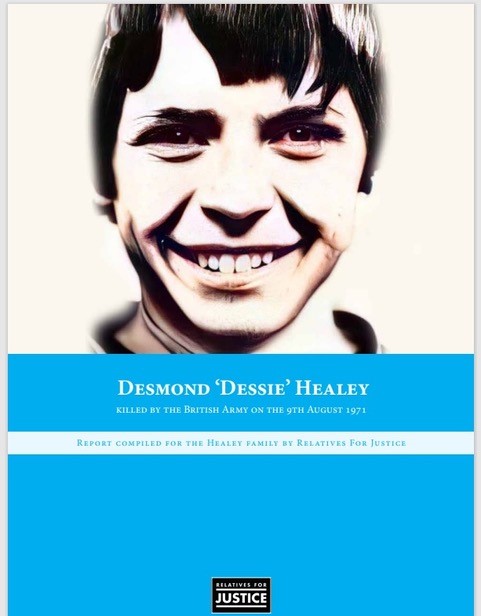

Dessie was 14 years old when he lost his life – a child, a schoolboy who was full of life as described by his family and friends, who loved dancing and swimming. His life was cut short on the 9th of August 1971, on the dreadful day known as the introduction of internment, when he was rioting against soldiers of the Parachute Regiment, the elite airborne infantry of the British Army which was also responsible for the unjustified deaths of 11 innocent people in Ballymurphy. Led by Coroner Maria Dougan, the inquest into the death of the schoolboy is currently looking into the circumstances in which Dessie was killed. The Healey family is represented by barristers Fiona Doherty KC and Orla Gallagher, instructed by Ó Muirigh Solicitors, who secured the inquest for Dessie’s relatives. The other parties in the inquest are the Ministry of Defense, the PSNI, and two former British soldiers known to this inquest under the cyphers of M66 and M23.

Throughout the months of December 2022, and January, August and September 2023, the Coroner has heard the evidence of 16 civilian and 5 military witnesses – former members of D Company, 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment – as well as many other testimonies collected in statements which were read out in court under Rule 17. Some of these statements were taken by the Association for Legal Justice (ALJ) in 1971, and others more recently by the Coroner’s investigator. Although some of the details given in those narratives vary, most probably due to the passage of time, the historically disputed circumstances remain the same when comparing civilian and former military testimonies. Other factors include the traumatic experience observed by the witnesses – who were mostly children and young adults at the time.

The civilian witnesses are all clear that rioters in Lenadoon Avenue, the majority of who were teenagers and young adults throwing mainly stones and empty bottles, did not have nor did they throw any petrol bombs at the British Army as originally reported by the soldiers, and none of them have a recollection of having heard any warnings being given by the Paras.

It is believed that Dessie had just thrown a bottle at British soldiers and was about to propel another one when he was shot. Some civilian witnesses have a clear recollection of what his latest projectiles were – HP sauce bottles, which are believed to have been brought to the area from a hijacked food lorry close by. The military involved in Dessie’s death at the time gave statements to the Royal Military Police and said he was throwing petrol bombs. None of the former British soldiers who had witnessed the shooting and given evidence in court could say they had seen petrol bombs being thrown – only one, known to the inquest as M63, mentioned having smelled petrol in the vicinity. The military witness cyphered as M66, however, corroborated the recollections of civilian witnesses during his evidence – he did not see petrol bombs, nor did he smell any petrol in the area, and he never heard any warnings being shouted by his colleagues. This, we believe, would suggest that the Paras may have acted in contravention of the Yellow Card and the rules of engagement contained in it, which the now Lady Chief Justice Dame Siobhan Keegan found their colleagues in C Company did on the same day in Ballymurphy.

M66 also admitted that he knows the name of the British soldier who fired the fatal shot, known to this inquest only as Soldier D – he has not yet been identified – but he refused to disclose the name to the Coroner, even though he could be found in contempt of court as a consequence. This is one of the outstanding issues that the inquest is now dealing with at the final stages of the inquest, before the parties prepare their written submissions for the Coroner’s consideration in the coming months. A date is expected to be fixed and the outstanding issues heard and dealt with in due course. Coroner Dougan will then be expected to deliver her findings before the cut-off date given by the Legacy and Reconciliation Act. In fact, the Healey inquest could be one of the last ones to be concluded before all the current mechanisms are shut down by the Act of Shame next year.

During this challenging but hopeful process for the family, we have seen that the pain and trauma of having witnessed the violent killing of a child has transcended Dessie’s relatives. The bereaved are legally entitled to truth and justice as enshrined in international human rights treaties and standards.

We also believe there is a moral responsibility towards the wider community who are impacted by the loss of their schoolfriend in this appalling killing. That truth extends to the immediate surviving witnesses who were also children when Dessie was killed. They too carry the traumatic impact of that fateful day with them. And then there is the wider communal impact that has been so layered with traumas given the extent of the conflict that only accountable truth and justice – with culpability – can deliver to in terms of historical clarification that ends the State lies.

That is why we need ECHR Article 2 compliant mechanisms to deal with past human rights violations, and the so-called Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery is not one of them.