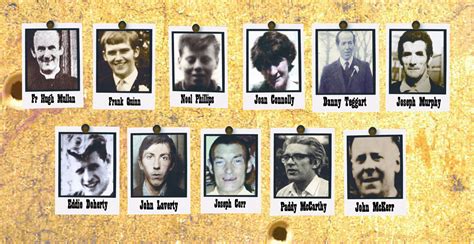

Mrs Justice Siobhan Keegan has now delivered her findings in respect of the deaths of ten people in Ballymurphy from 9 to 11 August 1971 on the first days of Operation Demetrius (internment without trial). She has vindicated the campaign by their relatives to have the official record of their deaths corrected, that they were innocent victims who should not have been shot dead.

Over the course of two and a half hours, she calmly outlined her findings from 100 days of evidence – making this the longest ever inquest in this jurisdiction. She was able to find, on the balance of probabilities, that they should not have been killed, that their deaths were unjustified and that the state failed to investigate the deaths in a manner which would have settled definitively what took place. This was a thorough accounting, over 600 pages in length. This was the first time, 50 years after the events, that a full examination of the ten deaths could be said to have taken place.

This is how a state should operate when it kills citizens.

As is now well known the killings took place over five separate incidents and her findings were delivered in the same fashion.

In the first, Fr Hugh Mullan and Frank Quinn were killed on a piece of waste ground that had been used as an escape route from the mixed housing development of Springfield Park to Moyard, by Catholic families from loyalist attacks.

Bobby Clarke, who was assisting families flee to safety across the field, was shot and injured. Fr Mullan came to his assistance waving a white cloth. He was shot. Frank Quinn also went to their aid, and he also was shot. Both men died within minutes of these injuries. Bobby Clarke survived the attack. Despite claims that they were gunmen, Mrs Justice Keegan found there was no such evidence, and nor was there any justification for opening fire on them. All distracting nonsense that the UVF may have been involved was dismissed. Father Mullan, far from a “gunman” was described by Justice Keegan as a Peacemaker, something his family, especially his brother Patsy has always known. Frank Quinn was a hero – he had gone to the aid of Father Mullan without thinking of his own safety. His name is now vindicated. His brother Pat remembered their parents who never recovered from Frank’s killing yesterday in his poignant tribute.

The second incident took place near the British army base at Henry Taggart Hall. Joan Connolly, Daniel Teggart, Noel Phillips and Joseph Murphy were all killed separately by the British army. In respect of these deaths, the fact that no military witnesses came forward to give evidence meant that the judge placed less reliance of their testimony. In any event, a careful analysis allowed her to conclude that, though there was “undoubted IRA activity”, none of the deceased were involved in any such activity, disproportionate force was used and the deaths of these entirely uninvolved civilians was completely unjustified.

Importantly Justice Keegan concluded that the victims’ bodies were not treated with respect and suggested that the young soldiers appeared to be of the view that everyone in the area was in the IRA, drawing no distinction between IRA personnel and civilians.

The Coroner added that there was basic inhumanity shown by soldiers to the injured, including Joan Connolly, who felled by 3 to 4 bullets, one of which took part of her face off, was left to die despite her plaintive cries for help. She described the treatment of injured and deceased in the Henry Taggert Memorial Hall as “heavy handed”, “triumphalist” and “abusive”.

Briege Voyle in her press conference statement described her mother Joan Connolly as guilty of nothing except love for her daughters. Alice Teggert remembered her joking loving father whose loss was compounded only a few years later when their brother Bernard was killed by the IRA, her family now has truth for both devastating incidents. The Philips’ family expressed their overwhelming reaction to vindication after years of struggle for truth. Janet Donnelly described her journey for the truth of the killing of her father Joseph Murphy as having taken over their lives and how now they begin a new chapter for accountability.

The third incident took place at a barricade on the Whiterock Road, erected to prevent British soldiers accessing the area. Edward Doherty was killed there. A soldier in a military tractor was trying to dismantle the barricade, and two or three petrol bombs were thrown. The soldier opened fire, killing Eddie. The judge said that Eddie Doherty was not involved in any violence and his shooting was unjustified. Even though the judge accepted that the soldier might have felt he was under threat, he gave no warning, fired but did not aim his shots, with a burst of fire from his machine gun. Justice Keegan further noted the soldier changing his version of events several times. In these circumstances, the killing of Eddie Doherty was entirely unjustified. Eddie’s sister thanked the Lord Jesus Christ for the support to help her through 50 years of trauma.

John Laverty and Joseph Corr were killed in the fourth incident which took place in the early morning, around 4.30am, of 11th August in Dermot Hill as soldiers descended a track down from the mountain called the Mountain Loney. For this incident, the judge relied on civilian testimony and the evidence of army medics to find that, while there may have been more people in the area initially due to warnings about the arrival of British soldiers and loyalists, about to attack the area, there is no evidence that the soldiers had been under threat to justify shooting. There was no disturbances at all at the time both men were shot in the back as they were crouched or crawling away from the soldiers. Carmel Quinn, John Laverty’s sister, said her brother was killed and it was never investigated because the state did not care. But the family and their supporters had always cared and now they begin the search for accountability. Eileen Corr, daughter of Joe, described the impact of the loss of her daddy on her siblings and especially her mummy, their lives never recovered.

The fifth incident was the most opaque. John McKerr, a former British soldier, was shot dead as he came out of the chapel where he was at work. Mrs Justice Keegan was highly critical of the lack of investigation into the death of this civilian father. This was shocking and constituted an abject failure on the part of the authorities and is an indictment on the state. There are no military witnesses and none of the civilian witnesses could be sure of the provenance of the shot by which he died; the ballistic experts could not be certain whether it was a low or high velocity shot. However, there is no evidence that John McKerr was other than a completely innocent man shot down while innocently going about his work. His daughter at the emotional press conference described the relief at having her father’s name cleared.

What can we draw from all this?

We must pay tribute to the families and their lawyers who had to wage a hard campaign to vindicate their loved ones.

These findings are an important acknowledgement of the standard practice that those the state killed during the conflict were generally accused of being gunmen/women, criminals, suspect – in order to exonerate the military or the RUC.

These lies would have been impossible if prompt, thorough and impartial investigations had been undertaken. State impunity perpetuates the lies.

It is significant that in the case of Daniel Teggart, the presence of lead residue was not sufficient to make a finding that he had handled weapons or been near someone firing a weapon. This has been a standard piece of so-called evidence in many British army shootings during the conflict. Indeed, a quantity of ammunition was planted by soldiers on Daniel Teggert to further impugn him and justify his killing.

Mrs Justice Keegan used the standards of domestic and international law, Article 2 of the ECHR. This requires independent, prompt, transparent, thorough, impartial investigations during which the family’s interests are borne in mind and they are kept informed of developments. This is particularly the case where the state takes life. The judge acknowledged that this is required now because it never happened at the time or since. The families’ testimony was that they were viewed as the enemy, even though two of the victims had served in the British armed forces. A 615-page set of findings is testimony to the new environment that exists, with families having proper legal representation and the inquest able to probe the evidence to the extent possible and required.

Contrast this with the British government’s current proposals to truncate Article 2-compliant investigations into conflict-related deaths and protect former soldiers from having to appear in the courts. It is notable that, where military witnesses did come forward to this inquest, their testimony was considered fairly and, where consistent, was relied on and carried weight. Mrs Justice Keegan notably could give little weight to soldiers’ testimony if they did not attend so that she could assess their evidence in person. Similarly, because their evidence could not be tested under questioning, it could not be relied upon, in the absence of other concrete evidence. The fact that so many civilian witnesses came forward, gave their testimony in person and submitted to cross examination gave their accounts greater force. Civilians spoke truth to power and they were believed. The soldiers that hid had their version of events dismissed.

Ten violent deaths in such a confined area over a mere 72 hours burned into the consciousness of the community. 57 children lost a parent. The British army’s role as oppressor was cemented. The knowledge that Catholic lives were expendable ensured that conflict would be prolonged and peace would be harder to achieve. The lesson that British forces would not be made accountable from those early days was understood both by the British military, from the generals down to the squaddies; but also by the Catholic community. Had the soldiers been held to account immediately, Bloody Sunday could not have happened and the course of the history of our conflict might have been very different. State impunity accelerated and prolonged the conflict.

After 50 years, in the case of the victims of the Ballymurphy Massacre, this inquest has provided some vindication for their memory and their families. And it has given hope to other families, especially other families affected by state violence.

All of the families spoke of their relief at having at last achieved the rewriting of the official narrative, and their determination to secure justice for their loved ones.

Importantly each and every family remembered Paddy McCarthy – the hero community worker whose ill treatment led to a heart attack and untimely death. He is the 11th victim of the Ballymurphy Massacre.

In the British army’s attempts to subjugate, humiliate, torture and murder the civilian population of Ballymurphy in 1971 and in their consistent attempts to thwart these families’ search for truth, they have exposed themselves as inhumane aggressors and cowards.

It is important to remember that 17 people were killed that day and all victims need and deserve access to truth and justice.

But accountability is required now – for all families affected by all actors. Amnesty legislation must now be taken off the table. In the words of the formidable John Teggert: “Only those afraid of the truth want amnesty”.

The families of Fr Hugh Mullan, Frank Quinn, Joan Connolly, Noel Phillips, Danny Teggert, Joseph Murphy, Eddie Doherty, John Laverty, Joseph Corr, Paddy McCarthy and John McKerr deserve this verdict and deserve society’s thanks for re-setting the moral compass of the debate on the past.